Urbanization is typically accompanied by a decline in biodiversity, yet certain species seem to thrive in urban areas where features of the native ecosystem have been greatly altered. In the Phoenix metropolitan area, the western black widow spider (Latrodectus hesperus) has become an urban pest, forming dense populations in the city. Since the venom of widow spiders is particularly dangerous to humans, their presence is not welcome in these human-shaped habitats. Instead, black widows are a factor in a vigorous pest management industry that homeowners depend on to rid their homes and yards of spiders, scorpions, roaches, and other undesirable arthropods.

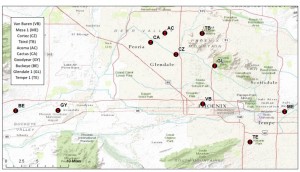

CAP scientist Dr. Chad Johnson and his students, Patricia Trubl, Lindsay Miles, Meghan Still, and Theresa Gburek, have studied the western black widow for the past seven years. Their work focuses on the ecology, behavior, life history, and genetic make-up of urban widows versus their desert dwelling counterparts. Some of this research takes place in field locations around the Phoenix metropolitan area and surrounding desert where widow populations are monitored (Figure 1). Johnson and his team also collect spiders in urban and desert locations and house them in enclosures at the ASU West campus and in the Johnson lab. This enables them to closely observe behavior, measure physiological characteristics, and conduct experiments with the spiders.

The plethora of pest control companies ready to exterminate black widows and other pests suggests both a low tolerance for these arthropods and an abundance of them in the city. In one investigation, the Johnson lab found that black widow spider density was 30 times greater in their urban research site (0.19 spiders/m2) than in the desert site (0.006 spiders/m2). They also discovered that urban spiders lived closer to one another (nearest neighbor distance) than those in the desert with urban webs sometimes in close proximity to one another.

Other research by the team showed that even within urban areas, there is great variability in habitat features, which has implications for the size of black widow agglomerations (infestations). As black widows use chemical cues from common prey (crickets, cockroaches, ants, and beetles) to track their next meal, they tend to set up house and weave their three-dimensional webs in areas that contain those cues. CAP research on insects and other arthropods suggests that the abundance of such prey is likely the result of intensive irrigation in the city. Therefore, the profusion of urban widows may be a response to the creation of the “desert oasis” in Phoenix, although the Johnson lab’s work thus far has not found a clear relationship between the abundance of vegetation and widow populations.

Johnson and his students have also investigated the life history characteristics of urban and desert widows as a means of teasing out the impacts of urbanization on the species. While the availability of prey was positively related to the weight (mass) and population density of urban widows, female urban widows were significantly smaller in terms of mass than those from the desert. When the team compared egg sacs, desert widows had heavier sacs containing more eggs. Urban widows appear to be investing less in off-spring than their desert counterparts even in the face of abundant prey.

The Johnson lab is working to understand these results. One possibility is that despite urban prey abundance, urban spiders face stiff competition as the size of their populations grows. The result of this could be a cycle of boom and bust for widows as smaller populations grow rapidly until competition (and perhaps cannibalism) begins to slow their growth. Yet the team has seen crickets hop through urban widow webs with no dire consequences, suggesting that competition has not left urban widows hard up for food. They propose to test another hypothesis that the nutrient composition of widow prey is compromised in the city, which might explain the poor condition of urban widows.

Recent investigations of western black widow population genetics have yielded other surprises. Working with Dr. Brian Verrelli, the research team has found dramatic genetic variance between urban and desert widow populations. Their preliminary analyses indicate that these two populations diverged approximately 1-2 million years ago, suggesting that the urban Phoenix widows are not descended from their Sonoran Desert neighbors and may have been transported to the Phoenix area unknowingly by people. Ongoing research is examining black widows from other southwestern cities to explore this finding.

Chad Johnson and his students are pursuing several strands of research to understand the variables that have resulted in urban black widow infestations, and they intend to use this knowledge to inform local communities on how to control widow populations without pesticide use. This investigation of the western black widow will contribute to our wider understanding about the dynamics of biodiversity decline under urbanization and the rise of certain urban “specialist” species, such as the western black widow spider.

References

Cook, W. M. and S. H. Faeth. 2006. Irrigation and land use drive ground arthropod community patterns in urban desert. Environmental Entomology 35:1532-1540

.Johnson, A., O. Revis and J. C. Johnson. 2011. Chemical prey cues influence urban microhabitat preferences of Western black widow spiders, Latrodectus hesperus. Journal of Arachnology 39:449-453.

Johnson, J.C., P.J. Trubl, and L.S. Miles. 2012. Black widows in an urban desert: City-living compromises spider fecundity and egg investment despite urban prey abundance. The American Midland Naturalist 168:333–340.

Shochat, E. 2004. Credit or debit? Resource input changes population dynamics of city-slicker birds. Oikos 106:622-626.

Shochat, E., W. L. Stefanov, M. E. Whitehorse and S. Faeth. 2004. Urbanization and spider diversity: Influences of human modification of habitat structure and productivity. Ecological Applications 14:268-280.

Trubl, P., T. Gburek, L. Miles and J. C. Johnson. 2012. Black widows in an urban desert: Population variation in an arthropod pest across metropolitan Phoenix. Urban Ecosystems 15:599-609.